Mourning customs in the Regency Era were less rigid than in Victorian England. The excessively strict mourning rules we often encounter in historical novels came about after Queen Victoria’s husband died — she wouldn’t give up her black mourning clothes and she turned mourning into a firmly followed rule of propriety. Her subjects used her example to springboard their own mourning customs. Keep in mind that these are not LAWS for mourning. Any display of mourning was done at a family’s or person’s discretion. However, there were social norms, that, if not followed, might raise some eyebrows.

In the excellent book, The Rise of the Egalitarian Family, Trumbach gives the following data for mourning periods:

12 months for a husband or wife

6 months for parents or parents-in-law

3 months for a sister or brother, uncle or aunt

6 weeks for a sister-in-law or uncle or aunt (no explanation for the duplication here so perhaps it had to do with the closeness or lack thereof

3 weeks – uncle or aunt, aunt who remarried, first cousin

2 weeks – first cousin (and whether they were close or not?)

1 week – first and second cousin, and husband or stepmother’s sister.

Trumbach says there was usually a designated female who kept up the family tree and ordained the degree of mourning required for the dearly (or not so dearly) departed.

Trumbach says there was usually a designated female who kept up the family tree and ordained the degree of mourning required for the dearly (or not so dearly) departed.

Bombazine and crepe were typical fabrics used for clothing of deep mourning. Crepe was a lightweight black silk, while bombazine was a medium-weight silk and wool blend. Over time, shinier fabrics emerged in the evening. The less wealthy simply took apart their clothes, dyed them black, then re-sewed them.

Mourning–or lack thereof–could also be used as an opportunity to get back at someone you disliked by cutting down on the time or style of one’s mourning.

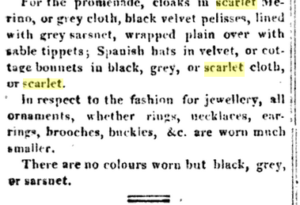

The widow would be in black for the first six months, and then in half-mourning (black and white mixed) for the next six months. After that, the widow would go into half mourning. White, grey, and even lavender were suitable for half mourning. Again these are ideals, and not everyone observed them. Ackermann’s had a half-mourning dress in a 1819 issue that was all white. Lavender is not mentioned in this issue, but it was commonly accepted as an appropriate half-mourning costume. On one blog I visited, I saw mention that there were some fashions circa 1811 of someone wearing scarlet for mourning, but “scarlet,” often a term used to describe items that are scarlet (red) in color, was also used to describe any brightly-dyed, plain-woven woolen fabric. I find it impossible to determine which meaning is being used when they say it was a scarlet mourning shawl, but I found this: February 1811 For the Promenade, cloaks in Scarlet merino or grey cloth, black velvet pelisses, lined with grey sarsenet, wrapped plain in tippets; Spanish hats in velvet, or cottage bonnets in black, grey, or scarlet cloth.

In March 1811, La Belle Assemblee Ladies Magazine said that scarlet mantels were much worn during mourning, and generally succeeded by short pelisses of purple velvet. Ladies Monthly Museum didn’t have any mention of scarlet.

From March 1811 page 100 La Belle Assemblee ladies magazine:

From March 1811 page 100 La Belle Assemblee ladies magazine:

For the promenade, scarlet mantles have been so general during the mourning, that for mere variety they must now he laid aside; we think they are more frequently succeeded by the short pelisse of purple velvet, trimmed with broad black lace, or small cottage mantlet, lined with while sarsonet, ornamented with white chenille or gold. Purple sarsonet pelisses, or black velvet, lined with colours, are equally approved.]

And here is this from the same magazine:

A round dress of white satin, sloped up in front; with small train ornamented round the bottom with velvet in a scroll pattern, vandyked at the edges, and dotted with black chemille; the velvet during the mourning should be grey or scarlet ; the bosom, girdle, and sleeves of this dress are ornamented to correspond, in the form exhibited in the plate. A turban cap of white satin, looped with pearls, and edged with velvet; the hair combed full over the face, curled in thick flat curls, divided on the forehead. No lace, earrings, and bracelets of gold and pearls blended. White kid shoes and gloves; fan of white crape and gold.

Princess Amelia died in November of 1810, and the official mourning went from November almost to March. However, scarlet mantles were definitely mentioned in January and March issues. Also, Diana Sperling in Mrs. Hurst Dancing shows her sister and her wearing bright red capes or large shawls. A later fashion description says that Scarlet capes are quite exploded but a later one mentions that they were still worn in the country.

Before you jump to the conclusion that they were all wearing red in the Regency during mourning, the term “scarlet” is also used to describe very fine, fancy fabric which goes back as far as the 13th century. So in this case, scarlet might also have meant very fine fabric–not necessarily red. What makes it more confusing is that the image above clearly shows a red pelisse. *shrug*

In THE WORKWOMAN’S GUIDE by A Lady (pub. 1840, long before Q. Victoria went into mourning) it says military men wore black armbands below the elbow, not above, and that affluent families put their servants in mourning etc.

The male servants had black bands tied to their sleeves and black ribbons on female caps. The male servants who wore gloves would wear black ones. Female family members would wear black gowns and somber coats and have mourning caps. Bonnets would have black ribbons. Most upper class families kept mourning outfits on hand considering that they often went into mourning for royals or a lost battle or a person like Nelson.

A bride would never wear mourning colors to her own wedding. In fact, a new bride was not supposed to be in mourning at all; though if her parents had recently died she might wear black or more sober clothes for a period, especially as brides were not supposed to go out socializing for a month after their wedding. Also, keep in mind that communication and travel were both slow, so the family may choose not to tell a bride on her honeymoon out of a desire not to ruin her wedded bliss, and because it was unlikely she could arrive home in a timely manner. Also remember, mourning during the Regency was an individual and family-dictated observance.

Julia Johnstone (before she was ruined and became a courtesan) had her court presentation and her debut in society not long after her father died, so clearly the world didn’t stop for people in mourning. However, while in full mourning, the family of the deceased typically avoided large, formal entertainment such as balls, dinner parties, and dances. They were expected to limit social obligations to necessities and church but apparently only for 4 to 6 weeks.

Julia Johnstone (before she was ruined and became a courtesan) had her court presentation and her debut in society not long after her father died, so clearly the world didn’t stop for people in mourning. However, while in full mourning, the family of the deceased typically avoided large, formal entertainment such as balls, dinner parties, and dances. They were expected to limit social obligations to necessities and church but apparently only for 4 to 6 weeks.

I have not found any references yet, but I do not believe anyone was presented in court while in mourning.

Men wore black armbands, black gloves and some wore black cravats. Some wore all black while in mourning. There is no mention of half mourning attire for men, however, there was mention of men wearing a white band or ribband (ribbon) on their hats to mourn a young girl.

Widows were not supposed to dance or to go to the more frivolous and silly plays while in mourning. Widows were not supposed to marry until a year had passed to end any doubt about the identity of a child’s father if she were found to be increasing, but many did remarry. This could cause a scandal but it was usually forgotten in a year or so.

Widowers did not have the same reason for waiting a year to remarry, and if they had small children, widowers were forgiven and even expected to remarry soon.

Other Ways to Signify Mourning

When notifying relatives of death, the announcement often came trimmed in black. I have also heard of the family mailing black gloves along with the announcement of death.

A hatchment or a mourning wreath would be suspended over the front door of a deceased person’s house for 6 to 12 months, after which it was moved to inside the parish church. The last recorded use of a hatchment I found was hung in a London street in 1928.

A hatchment or a mourning wreath would be suspended over the front door of a deceased person’s house for 6 to 12 months, after which it was moved to inside the parish church. The last recorded use of a hatchment I found was hung in a London street in 1928.

Closing the drapes and erecting the hatchment over the door. In Town, meaning London, black ribbon could be tied to the door and the hatchment could be put there if the deceased died in Town and would be buried from there.

There were no hard and fast rules about these things. It all depended on how the movers of society reacted. Men were criticized much less for such breach of propriety than women. What a surprise!

Only the length of public and court mourning was set out in a fixed manner. The Lord Chamberlain notified the Gazette as to what it would be. If anyone were invited to court during this time, they were also sent instructions as to what to wear.

Upon his mother’s in 1818, the Prince of Wales announced that he intended “to wear the longest mourning that ever son did for a mother…” then he actually limited the official mourning period for the people of England to six weeks.

I couldn’t find the official mourning proclamation for Princess Charlotte, but I did find this for the father of Queen Victoria, the Duke of Kent, who died in 1820:

Lord Chamberlain’s Office, Jan. 25.

Orders for the Court’s going into mourning, on Sunday next, the 30th instant, for his late royal highness the Duke of Kent and Strathern, fourth son of his Majesty, viz. The ladies to wear black azins, plain muslin or long lawn, crape hoods, chamois shoes and gloves, and crape fans. Undress.—Dark Norwich crape. The gentlemen to wear black cloth, without buttons on the sleeves or pockets, plain muslin or long lawn cravats and weepers, chamois shoes and gloves, crape hatbands, and black swords and buckles. Undress.—Dark gray frocks.

Herald’s College, Jan. 25.

The deputy Earl Marshal’s order for a general mourning for his late royal highness the Duke of Kent. In pursuance of the commands of his royal highness the Prince Regent, acting in the name and on the behalf of his majesty. These are to give public notice, that it is expected that upon the present melancholy occasion of the of his late royal highness Edward Duke of Kent and Strathern, fourth son of his majesty, all persons do put themselves into decent mourning, the said mourning to begin on Sunday next, the 30th instant. HENRY HOWARD – MOLYNEUX-HOWARD, Deputy Earl-Marshal.

Horse-Guards, Jan, 25. It is not required that the officers of the army should wear any other mourning on the present melancholy occasion than a black crape round their left arms with their uniforms. By command of his royal highness the commander-in-chief.

HARRY CALVERT, Adjutant-General.

Admiralty-Office, Jan. 25. His royal highness the Prince Regent does not require that the officers of his majesty’s fleet or marines should wear any other mourning on the present melancholy occasion of the of his late royal highness the Duke of Kent and Strathern, than a black crape round their arms with their uniforms. J. W. CHOKER

For more information on mourning clothing, I highly recommend The Jane Austin Centre.

Hi Donna , wonderful synopsis of Regency mourning – could you help me please – mourning for sons and step sons ( same individual ) , who died tragically ( Melbourne 1846 ) . An upper middle class family , moderate prosperity – 6 months mourning ? Was that customary ? Was it still the done thing to have ” hair rings ” made ? And how did the family ” receive ” – I believe callers were largely ignored by the female relatives , is that correct ? Any help very gratefully received , thank you , Warrick Lisle , Rosebud Victoria , Ausralia

Thanks for stopping by. 3 to 6 months is a very reasonable mourning period for a son or step-son and would not raise eyebrows for being too short or too long. By 1846, they probably had a an even longer half-mourning than full mourning. Remember, mourning was highly individual based on the person’s temperament and how close one was to the deceased. Do whatever works for your situation.

All kinds of jewelry made from the hair of loved ones were very popular from the through the Victorian Era–rings, broaches, watch fobs etc. and were lovely.

Callers were not ignored unless the lady was too distraught to receive, but women never attended a funeral or burial–that was strictly a male event since ladies were considered too delicate. They didn’t generally host or attend balls or large dinner parties during full mourning. A family dinner or a small dinner party for a few close friends was deemed acceptable.

Does that help?

I saw some colored fashion pictures in 1810/1811 with scarlet shawls — colored scarlet- amazed me. After the mourning for Princess Amelia there was a fashion note that said scarlet shawls were much exploded. Before that, in discussion of the morning for the princess, scarlet shawls were mentioned. In Mrs. Hurst Dancing the girls wear scarlet shawls. It was very fashionable around 1810/1811 . Perhaps ladies didn’t want to give up their favorite shawls for a princess whom they didn’t know. Those in personal mourning, probably didn’t wear scarlet.

I would love to see those fashion pictures, Nancy. If you remember where you found them, please let me know!

La Belle Assemblee — I am pretty sure it was in that magazine. In December of 1811, the notes mention scarlet mantles edged with fur to be worn with a Mary Queen of Scott’s hat. Will look for the illustration I saw. I have it at home but don’t know if the source is included.

Now I really need to see this! I haven’t heard of a Queen Maryof Scott’s hat. I can’t wait to do some more exploring!

Great article! Thank you so much for all your thoughtful time and effort on this subject.

Would there be open coffins at the time. Did visitors go to the home of the deceased? How many days before burial?

There were open coffins for the wealthy who often were laid in state in the drawing room until members of the family could come and pay their respects.

There were undertakers who did a bit of preservation of the body to retard rotting but they were expensive and not all could afford it.

One book on Death in England said that the body of the poor often decomposed in a corner of the room until they could afford the cost of burial.

However, many poor rented a coffin, had the deceased sewn into a wool shroud, and buried as soon as the grave could be dug. The coffin had an open end and the shrouded figure would be tipped into the grace and then covered up while the coffin was used again by another.

Some people with ice houses put the corpse there until family could be notified.

The College of Arms Heralds thought they should have a say in the funeral of peers but often weren’t unless it was a state funeral.

A corpse could remain unburied longer in the winter than in the summer and sometimes had to wait for the frozen ground to be loose enough to be dug up.

If a person was to be buried in a private mausoleum the time of burial wasn’t as important as if the person was to be buried in the church yard. Of course, most church yards had been dug up so much the ground never got as frozen hard as it did elsewhere.

People generally did go to the home of the deceased or of another for “the funeral meats.”

This was a great font of information for me, as I have a story idea that would encorporate regency era mourning customs. Can I just ask though: If a widow of a middle to upper class family was 8 months into her mourning year, what social niceties could she perform to get to know any tenants with urgent on her estate?

Again, I apologize for taking so long to reply. To answer your question, keep in mind that the Regency mourning custom was not as strict as the Victorian Era. After 8 months, she might continue to wear black or she might transition into “half-mourning” which included grey, white, and lavender, but that was more common in the Victorian Era. She might even go right into regular clothes after six to nine months. Some may criticize if she did, but most probably wouldn’t. Manners and mores were more relaxed in the country than in London. Her activities were not that limited–dancing would be frowned upon as would be attending huge ball–but she could still socialize and attend to her duties as the lady of the big house attending to the needs of her tenants and paying visits to them. Does that help?

This was a great font of information for me, as I have a story idea that would encorporate regency era mourning customs. Can I just ask though: If a widow of a middle to upper class family was 8 months into her mourning year, what social niceties could she perform to get to know any tenants with urgent issues on her estate?

I apologize to taking so long to reply. I didn’t see your comment until just now. Mourning was not as strict and formal during the Regency as it was for the Victorian Era, so much was left up to individual families to observe mourning practice–depending on their relationship with the deceased. She could do anything for her tenants at any time–especially any urgent issues. It was mostly large gatherings, formal balls, etc. that she probably would avoid or she might be under social scrutiny. Also, the social manners and mores were more relaxed in the country than in the city. She would be most likely to visit them one at a time and bring baskets or boxes of food. She might also throw them an outdoor dance, but not dance herself. Also, if she’s a landowner, her land steward would likely take care of any issues with tenants; her role is mostly one of social–visiting the sick, admiring new babies, bringing food, and letting them know she is a benevolent landlady.

Thank you for this very helpful article!

I wonder at the lack of brother-in-law in the list of how long one should be in mourning? I am writing a story in which one character’s brother-in-law has been deceased for three months–would the living character’s carriage still be draped in mourning?

Hi Hannah. Thanks so much for your question. The short answer is: it depends. It depends on his relationship with the deceased (meaning, were they close?), his wife’s relationship with the deceased, any family customs or local customs, and his own personality and how worried he is about what people might think. The Regency is much less regimented than the Victorian era so there was more flexibility. By three months, most mourning customs had eased. Also, if he’s traveling, he may not broadcast a personal loss to strangers, or he may want everyone to know. Does that help at all?