Those fortunate few who lived in the glamorous, ephemeral world of the upper class in Regency England enjoyed luxury the likes of which most of us modern-day, working-class people can only try to imagine. Gowns that cost more than most workers made in a year, gilded carriages pulled by fine horses, jewels rivaling that of royalty, castles filled with an army of servants all belonged in their world. One of the many extravagances the Regency elite enjoyed was fine dining.

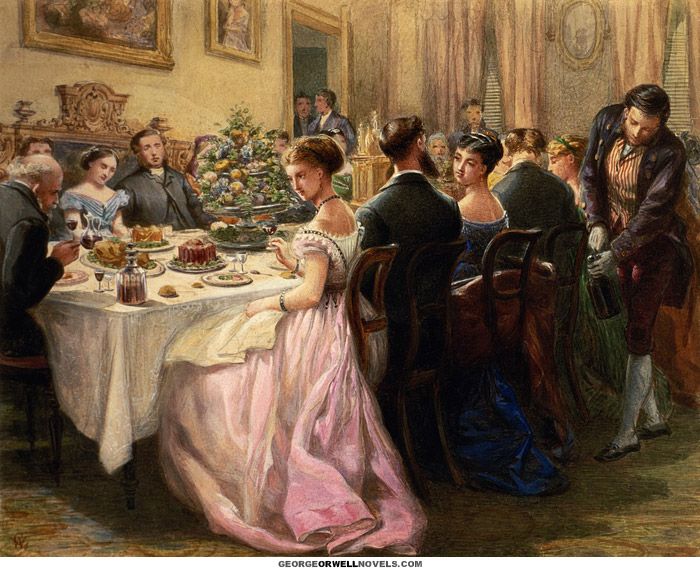

Their dinner parties were more complex and decadent than I have ever enjoyed. Even our traditional American Thanksgiving feasts are paltry compared to what the beau monde expected to see at a formal dinner party, which they seemed to have hosted and attended frequently—at least during the London Season. Between five and twenty-five courses made up a Regency dinner party, depending on the host’s wealth and the occasion.

Dinners could be served one of two ways, depending on the host’s preference, the formality of the meal, and the popular methods of that time. Service à la francaise is serving all dishes on the table at the same time, except for dessert, which seemed to have been popular prior to and early in the Regency era and in country homes. It’s how I serve meals in my own homes–I just didn’t know that it had a fun term.

After 1815, especially in London where things were often more formal, dinner parties were service à la russe, a practice of serving food in separate courses, removing one before replacing it with another. This method seemed to have become more popular later in the Regency Era. A highly celebrated chef named Carème who cooked for the Congress of Vienna is credited with introducing service à la russe. Since the upper class always strove to keep up with what was most fashionable on the continent, his method caught on among the nobility and gentry.

The French Cook (1822) gives a discourse on French cuisine which mentions “removes,” dishes that are removed from the table and replaced with other dishes. According to the author, there were seven classes of foods or courses, and that for a dinner party of eight “you cannot send up less than four entrees, a soup, and a fish.”

If the dinner was service à la russe, a variety of soups arrived first on the table. Some sources say fish was also served during the first course. If a guest wished to sample a dish placed out of reach in another part of the table, a servant served the guest. Many diners probably contented themselves with the dishes in their section of the table. However, an attentive gentleman might serve himself and those around him–but would never fill a lady’s plate too much lest she be viewed as having an unladylike appetite.

When the diners were finished with the first course, the hostess signaled the servants to clear the table and reset with remove–a collection of as many dishes as before. The second course consisted of an assortment of mutton, beef, and poultry as well as vegetables, and savories. One role of the host was to carve the meat which he served to himself and then each of the guests. I can only assume that attending servants carried the plates to each guest.

A combination of savory and sweet dishes tempted the palate next which included salad, cheese, pickles, jellies, and vegetables.

The tablecloth was usually removed for the final course– dessert (a.ka. “pudding”), which often included such delicacies as tarts, cakes, more cheese, nuts, custards, curries sweetmeats, nuts, souffle cakes, wafers, and flavored ices–often magnificently carved. Fruit was also a popular dessert item including grapes, strawberries, preserved fruits, preserved cherries, greengages (a type of plum), and melons.

One fun fact is that pineapples often graced the table of a formal dinner party, but not for eating; it was a table ornament. Because pineapple was so expensive and rare, a hostess would literally rent a pineapple to put on her table just to show off her wealth. I wonder if any hostess had to backpedal if a guest asked to eat it? Perhaps they all knew better. Then, why do it? Expectations, I presume. But I digress.

Wine and other alcoholic beverages were served with every course, which both genders consumed. A lady was expected to wait for wine to be served to her rather than asking for it, and to limit her consumption or she might be viewed as having the unladylike quality of drinking like a man. Horrors!

Copyright Donna Hatch

After the guests appeared to be finished with dinner, the hostess stood and led the ladies to the drawing-room to freshen up and enjoy gossip. The gentlemen remained in the dining room to enjoy alcoholic beverages and snuff while discussing topics considered unsuitable to the delicate sensibilities of the fair sex.

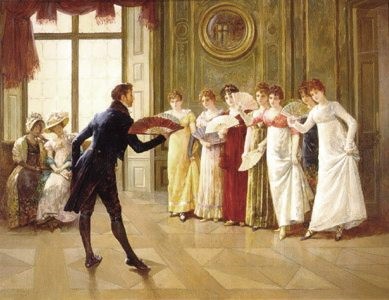

After the gentlemen joined the ladies in the drawing-room, they chatted, flirted, and played games or cards. Tea or homemade punch might be served. In some instances, guests chose to enjoy a small after-dinner dance, which often required the furniture to be moved and the carpets to be rolled up. Can you imagine dancing on such a full stomach? Dinner parties such as these lasted late in the night and sometimes until dawn.

Do you have a sudden urge to eat and then go dancing?

Always a pleasure to read the history you so elegantly write! Thank you!

Awww, thank you so much, Raeni!

I found it confusing to read of “covers” at a meal. Were they the same as removes do you think? I suspect they must be. I have also read of a “silver clouche” (spelling?) and wonder if that was the metal covering over a remove when it is brought to the table. Each author seems to use their own style of describing a meal and it is hard to imagine how it was really done. Thanks for your lovely descriptions of what you find in your searches for authenticity.

I think part of the confusion comes from the fact that different families had their own way of doing things. Some of those were due to where the parents were raised. Some were customs they developed, partially due to personality and partly due to income. So really, the fact that authors describe it differently only lends a realism to it. I haven’t encountered “covers,” but I agree with your possible explanation. A silver cloche is a dome lid used to keep the food in a platter warm during the trip from the kitchen to the table, which, in some houses, was quite a distance. I assume most of the dishes brought out during each course or remove had one.