English marriage, and the methods in which one could place one’s neck in the “parson’s noose,” underwent a number of changes just prior to the Regency. They changed again during the Victorian Era. Though a Special License appears frequently in romance novels, during the Regency Era, it was issued rarely, and only under extenuating circumstances. Let’s explore the licenses available to begin wedded bliss.

Putting up the Banns

During the Regency, the most common way to get married (especially among the humbler classes) was to have the banns posted. This was also called “putting up the banns.” This required posting on the wall of the church and reading by the clergy from the pulpit of both the bride’s and the groom’s parish churches for three consecutive Sundays in order to give the public a chance to object to the marriage. The two parishes had to send written confirmation to each other that a party from each parish was eligible to wed. After putting up the banns, a couple could get married within 90 days, and the wedding had to take place between 8:00 in the morning and noon in either the husband or wife’s parish of the Church of England, even if the couple were Catholic. Quakers and Jews were exempt, apparently.

Ordinary License, Common License, Bishop’s License

A couple wishing to marry could also do so by ordinary license called the Common License which a couple could obtain from any bishop. This did not require putting up the banns because the couple (or parents if one of them were under the age of 21), had to give a sworn statement that there was no reason they couldn’t marry. There was a small fee and it had many of the same restrictions of marriage by banns. This was the common way for a wealthier couple to marry or if the couple didn’t want to subject themselves to public protestation or a public wedding. For marriage by banns or a marriage license, the couple had to marry in either the bride’s or the groom’s parish. They could not simply marry in their friend’s drawing room or a garden, or other places I often see in fiction.

Special License

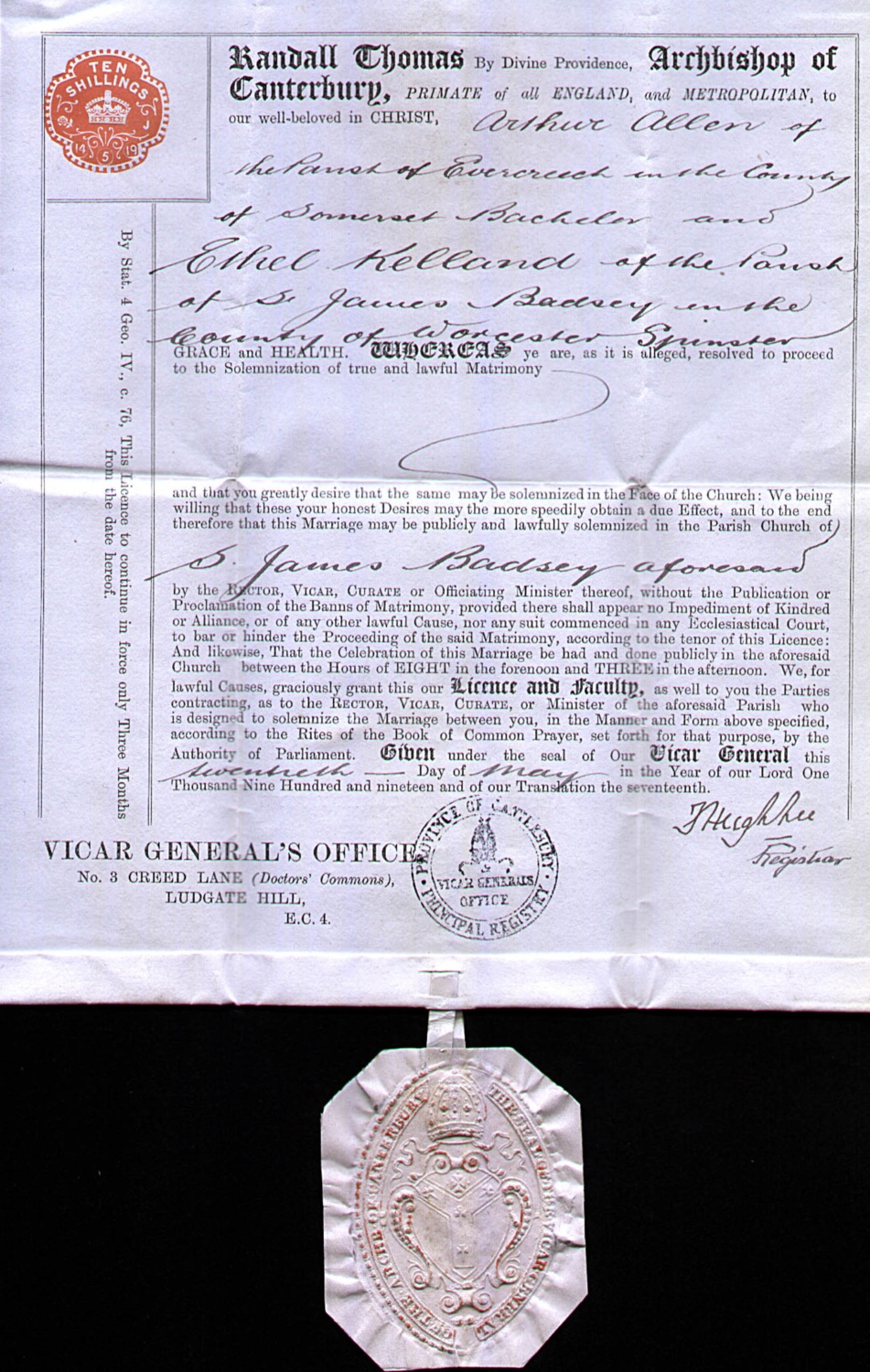

Special License

Marriage by Special License was different. The advantages of having a special license were that a couple could marry at any time and place that they wished as long as the marriage was performed by clergy and there were witnesses present. When applying for a special license, certain criteria must be met. First of all, few outside of titled lords and their spouses and children were eligible, and one seeking such privilege must go appeal to His Grace, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

According to noted researcher and novelist, Susanna Ives:

“BY the Statute of 23 Hen. VIII., the Archbishop of Canterbury has the power to grant Special Licences; but in a certain sense, these are limited. His Grace restricts his authority to Peers and Peeresses in their own right, to their sons and daughters, to Dowager Peeresses, to Privy Councillors, to Judges of the Courts at Westminster, to Baronets and Knights, and to Members of Parliament; and by an order of a former Prelate, to no other person is a special license to be given, unless they allege very strong and weighty reasons for such indulgence, arising from particular circumstances of the case, and they must prove the truth of the same to the satisfaction of the Archbishop.”

“In the case where the parties applying do not rank within the restricted indulgences, a personal interview should be sought, or a letter of introduction to his Grace should be obtained, containing the reasons for wishing the favour granted. Should his Grace grant his fiat, in either case, the gentleman attends his proctor to make the usual affidavit, that there is no impediment to the marriage—the same as in an ordinary license.”

Obtaining a Special License

When applying for a special license, both the bride and groom must be named so the Archbishop of Canterbury could verify their eligibility to wed. Since those who could use a special license were all members of the upper class, and since the archbishop sat in the House of Lords, His Grace probably knew most of them. Regardless, he would not have issued a license without verifying their eligibility to wed.

Contrary to some book plot devices, he never issued blank licenses to be filled in later, nor could they be transferred to someone else.

A special license costs quite a bit more than a common marriage license. It allowed a couple to marry in any location and at any time rather than in a church or between 8:00 a.m. and noon. With a special license, they could marry in their friend’s drawing room or a garden, or any other place of their choosing. As with an ordinary license, a special license so made the posting of the banns unnecessary, so if there were some reason a couple wanted to marry in haste or wanted to avoid a public venue in a church, the special license allowed a way to do it.

Remember, though, that obtaining a special license was dependent on the Archbishop of Canterbury’s decree and goodwill. His Grace didn’t grant Special Licenses frequently nor lightly as it took much of his time to do the necessary research.

Incidentally, there was no marriage by proxy in England during the Regency.

More information about the different methods available to the Regency couple wishing to marry can be found here.

Sources:

http://www.regencyresearcher.com/pages/marriage.html

https://reginajeffers.wordpress.com/2012/11/20/regency-era-marriage-customs/

Love these facts from history 🙂

I look forward to these tidbits of history. It is astonishing how much information is needed to write a book that follows the rules of the time.

I came here (via a Google search) after reading, perhaps, dozens of romance stories of the early twentieth century where special licence was mentioned. And, as Donna wrote, this licence was also erroneously used in many-a plot line.

HI Bret! Thanks for stopping by! Yes, you are right. But I try to give authors who use this a break. After all, if I waited until I knew everything about the Regency era before writing my first book, I’d still be unpublished.