The King is dead; Long live the King

When George III died on January 29, 1820, the official era we know and love as the Regency ended. Because a change in monarchy happens instantaneously, the Prince of Wales, George IV, immediately became king even though his coronation didn’t take place until July 1821.

Normally, the death of George III and the succession of George IV would have been publicly announced right away but the news didn’t reach London until night. By tradition, the announcement would have gone out the next morning. However, because January 30 was the day Charles I was beheaded, nobody wanted to risk association with that event. For that reason, the proclamation became official on January 31, although it would have taken months for the news to spread to the outer edges of the kingdom.

Mourning the Monarchy

The death of the monarch, beloved or not, came with an announcement of official mourning. The Lord Chamberlain published the style of mourning and the length of it for all those who attended the royal court. These strict instructions for Court Mourning only applied to those attending court functions. Those who sent in a request for a ticket to the Lord Chamberlain received directions for what to wear. It also came with a decree of what social activities could and could not continue.

What Not to Do

What Not to Do

Generally, as part of the mourning process, large entertainments, including theatre and opera (unless it was a religious performance such as those for Lent), soirees, balls, and large gatherings stopped after the death announcement and didn’t resume until after the funeral. Parliament also closed down until after the funeral.

Many people also curtailed these activities when Queen Charlotte was ill but I’m unclear if that was by decree or just out of respect.

Mourning Dress

Mourning Dress

According to Old Court Customs and Modern Court Rule by the Honorable Mrs. Armytage, this was how members of court were instructed to dress for mourning:

For the King and Queen: Deep mourning, Eight weeks. Mourning, Two weeks.Half mourning, Two weeks.

Son or Daughter of the Sovereign: Deep mourning, Four weeks. Mourning, One week. Half mourning, One week.

Brother or Sister of sovereign or wife: Deep mourning, Two weeks. Mourning, Four days. Half mourning, Three days.

Nephew, Niece, Uncle, Aunt, Cousin: Mourning, One week. Half mourning, One week.

Any other more distant Relations: Mourning, Four days. Half mourning, Three days.

Keep in mind, people often followed their own preferences so if a person were especially close to the deceased, they might mourn longer. Royals themselves sometimes wore purple to mourn other royals.

Rush, American Ambassador to the Court of St James, said in his book, Memoranda Of A Residence At The Court Of London Paperback, about his residence at the Court of St. James:

February 2. I receive from the office of the Lord Chamberlain, the following paper relative to a court mourning. A similar one was sent to all the ambassadors and ministers: I copy it word for word.

“Orders for the Court’s going into mourning on Thursday next, the 3d instant, for our late most gracious sovereign, King George the Third, of blessed memory, viz.; the Ladies to wear black bombazines ; plain muslin or long linen, crape hoods; shamois shoes and gloves, and crape fans. Undress — dark Norwich crape.

“The Gentlemen to wear black cloth, without buttons on the sleeves and pockets; plain muslin or long-lawn cravats and weepers; shamois shoes and gloves, crape hat-bands, and black swords and buckles. Undress—dark grey frocks.”

I had received a few days before, the orders for a court mourning in terms somewhat similar, for the Duke of Kent.” (who had recently died)

The Duke of Norfolk, or his deputy acting as Earl Marshal, sent out the instructions as to how the general population mourned a royal, specifically of what to wear and for how long. In reality, this just applied to high society and possibly the diplomatic corps in London. Those from the lower classes would not normally have the means to purchase mourning clothing, and their activities did not include those that were prohibited.

From the Elizabethan Era, wearing black was partially a way to show off wealth, since using the many dyes it took to create black would have been so expensive that until about the 1840s, the working class could not afford them. The middle class and less wealthy gentry dyed their gowns because dyeing a gown one already owned was less costly than purchasing a new black one.

I remember reading that Jane Austen wrote of dyeing a gown black because the Duke of Kent, the king’s brother and the father of future Queen Victoria, had died. I can’t recall exactly where. My guess is probably in her letters to her sister, Cassandra. I really need to take better notes. Or organize them more efficiently. If you know where that’s written, please tell me in the comments. But I digress.

Mourning Fashions

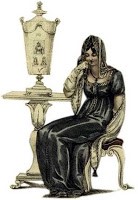

Fashion plates between February and April 1820 included mourning fashion. Mourning colors were black, grey, and black with white and grey. Deep mourning meant accessories such as gloves and hats were black as well. Jewelry was understated and might even include a lock of the deceased hair.

Prints for February show black or gray evening gowns with black gloves for deep mourning. The print to the right is described as a “black crepe round dress over a black sarsnet slip.” Crepe or crape, the official fabric of mourning (along with bombazeen), is extremely uncomfortable and stiff so putting it over a lightweight silk slip is a stroke of genius.

March and April fashion plates have black, gray, or black-and-white gowns worn with white gloves and black details such as black trim on a day gown or a black flower detail or even black stitching on a white evening gown. Some have white gowns with black shawls. This was in line with half-mourning. Half mourning also included pinstripe black clothing.

In the May issue, dresses are in full color again. In the print below to the left, the gown is pink and white.

When Princess Charlotte, heir to the throne, died in childbirth, the official mourning lasted for six weeks, with deep mourning for two, half mourning for two, and light mourning for two. Fashion prints for that era show black gowns and gloves for December. Costumes labeled “half-mourning” in January were black and white, with white gloves.

Some sources list lavender as a color for half mourning during the Regency while others claim that didn’t become a half-mourning color until the Victorian Era. I don’t see lavender listed as mourning attire in any of my fashion plates, but then, I don’t have an exhaustive collection.

Military

Naval and military officers are exempted from full mourning attired. They were instructed to wear black crape over the ornamental parts of hats, swordknots, and uniforms and to wear black waistcoats, breeches and stockings, wear black gloves, and a black band on the left arm.

Black bands on the arm are a common way for gentlemen, even outside the military, to mourn, a detail I’ve included in a few of my Regency romance novels.

Victorian Mourning

After Queen Victoria’s beloved husband died, she mourned him for the rest of her life by wearing black every day and living in almost total seclusion. She set a standard that many adopted during the Victorian Era and beyond. I hope Her Majesty and her beloved husband, Prince Albert, are happy together now.

I mention several of these mourning customs in my low-heat, aka “clean and wholesome” Regency Romances novels. I hope you check them out on my bookshelf.

More on Regency Mourning can be found here.

Sources:

Many thanks to fellow members of the Beau Monde: Allison Lane, Marissa Doyle, Nancy Myer, Nina Jarrett, Caroline Warfield for sharing their knowledge about Regency mourning.

Other sources:

What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew, by Daniel Pool

Old Court Customs and Modern Court Rule, available on Google books http://books.google.com/books?id=tX4PAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA181&dq=%22Court+mourning%22#PPA184,M1

Memoranda Of A Residence At The Court Of London Paperback by Richard Rush

The Atlantic, “The Elitist History of Wearing Black to Funerals” by Katie Thornton: https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2022/09/queen-elizabeth-funeral-black-dark-mourning-color/671558/

Images are from English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century by C. Willett Cunningham

Thank you for this informative article, Donna!

Though it’s a formal show of mourning, I can’t imagine being told, “Ok, time’s up! Let’s get on with the merriment!”

Mourning is personal, but yeah…