Few events created more anticipation and excitement, and in some cases, fear and dread, than the Season in London. Historically, going “up” to London for the Season coincided with the sessions of Parliament. The dates when Parliament convened varied each year but generally ran from January to July.

The varied beginning dates may have depended on the hunting season. According to What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew, no one would leave the countryside when hunting was good. “The Sessions of Parliament could not be held until the frost was out of the ground and the foxes began to breed.”

Once their country activities allowed peers and elected officials to attend to their duties in Parliament, they traveled to London to “sit” in the House of Lords or House of Commons. During this time, the Prime Minister and his cabinet introduced legislation, read in bills, and the Members of Parliament, or MPs, voted.

Due to difficulty traveling during the winter, MPs’ families usually stayed in their country homes, if they had them. Parliament adjourned during Lent, and most MPs went home for the week. They returned after Easter with their families to commence the dizzying social whirl known as the Season.

Entertainment

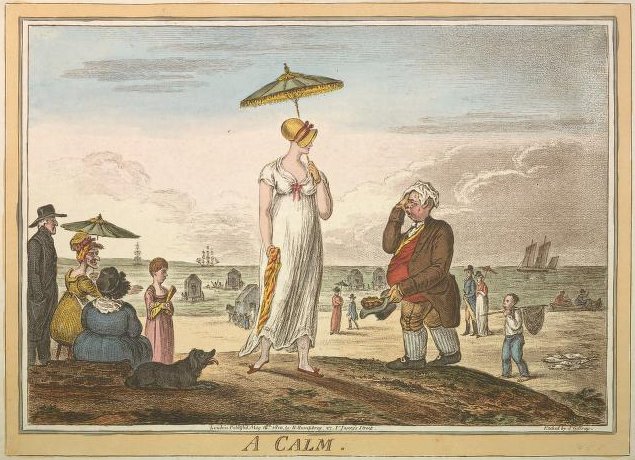

This gathering of the rich and powerful created a need for entertainment. These pleasant spring months made for ideal conditions to ride or promenade at the many parks, have garden parties, dine alfresco, and enjoy the companionship of friends and members of society. Events included balls, assemblies, the theatre, the opera, military reviews, parades, and celebrations (especially after Napoleon was defeated), masquerades, balloon rides (filled with hydrogen gas—not hot air), visits to a menagerie, viewing private museum collection, and a host of other public and private social events. In May, the Royal Academy of Art had exhibitions for viewing.

Making house calls was another important part of visiting London to make it known to friends that one has arrived in town. Activities also required a great deal of shopping, preferably in fashionable areas such as Bond Street, Portland Place, Cavendish Square, and Regent Street, or even in the new arcades, to keep up with the latest fashions.

In addition to the aforementioned activities, gentleman visited their clubs, purchased horses from Newmarket, and attended horse or boat races, and boxing matches. Some even engaged in rounds of fisticuffs and fencing matches.

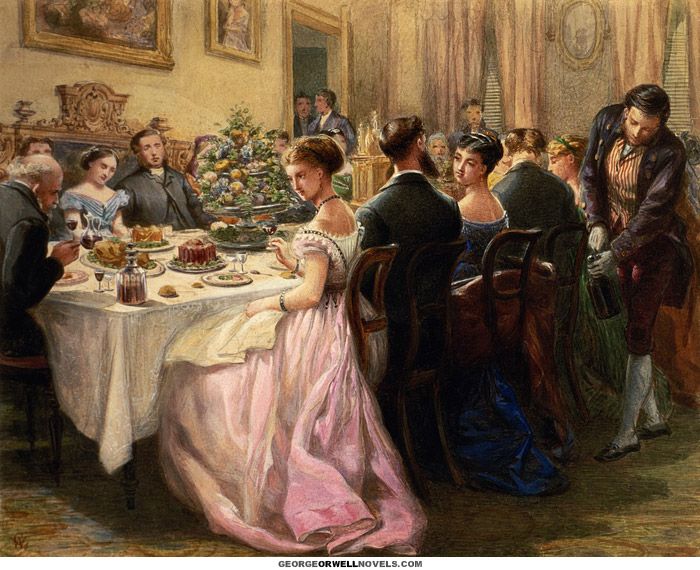

Hosting

Some hostesses considered it a status symbol to throw the first ball of the season, which took some maneuvering of dates. Too early, and not many of her desired guests would have arrived in Town yet so she would have poor attendance. Too late, and she might miss the opportunity to be first. Having all the right people at a dinner party or ball also presented bragging rights for the Season and reflected well on the family. This presented a huge expense and a great deal of work and coordination. However, a successful ball with a “crush” of guests helped with social, marital, and political alliances.

Meeting the Queen

During Queen Charlotte’s time as Queen of England, ladies who recently married peers were presented to the queen in a ceremony known as the Queen’s Drawing Room. There, a lady dressed in an elaborate court dress and bowed to the queen then backed away.

Queen Caroline never held Drawing-rooms, so there was a gap of court presentations during her reign. Also, no Drawing-rooms were held during Queen Charlotte’s illness or after her death. Queen Victoria resurrected the tradition of inviting ladies to be presented to her. During the Victorian Era, which is after the Regency, wives and daughters of peers, military men, barristers, and physicians might also take their bows. Supposedly, this was to advise the monarchy of their change in martial status, but also reflected well on the young lady to have been presented.

The Marriage Mart

Marriage was serious business. It involved creating an alliance with families of equal or greater wealth, power, or status. Finding true love took a back seat to finding the right connections. A fortunate lady married a man of honor who would be faithful to her. However, by the Regency, love—or at least affection—started to become more of a factor in an ideal match than in previous eras.

For those who had children of marriageable age, the Season presented a prime opportunity to introduce their children to the marriage mart. Meeting the right people at the right places helped secure an introduction to those deemed most desirable, and many activities centered around that endeavor.

A lady who was socially “out” sometimes bore the shame of having multiple Seasons which meant she was less desirable marriage material. Many families could not afford more than one or two Seasons, so returning home without a marriage proposal could have long-lasting results. Reduced prospects in the sparsely-populated rural areas often meant a life of dreaded spinsterhood.

Residences

Wealthy families often had homes in London or the surrounding areas where they stayed during the Season. Others rented a home or stayed with friends. The most fashionable places to live were in the West End–Mayfair and Pall Mall near where Buckingham Palace now stands. Incidentally, Grosvenor Square in Mayfair is pronounced “Grahvnur.” (It sounds better if one sticks one’s nose up a bit.) Mayfair is remarkably small and can easily be walked. It is no wonder most of the beau monde knew each other—not only did they socialize every Season but they were neighbors while in London.

Dancing

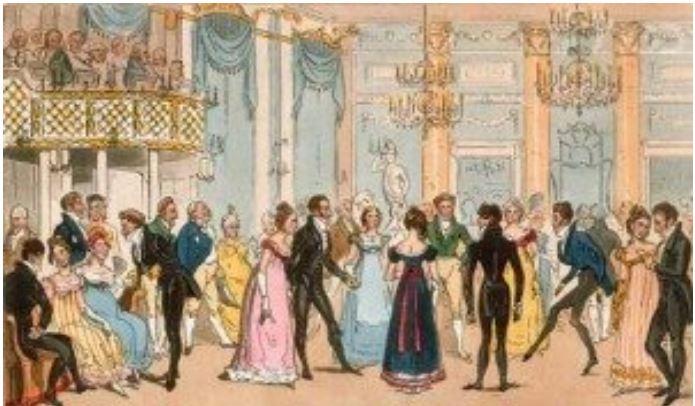

Every member of the upper classes knew how to dance, and most of the working class did, as well. Dancing was so essential to social events and finding spouses that there are records of the military officers being taught to dance.

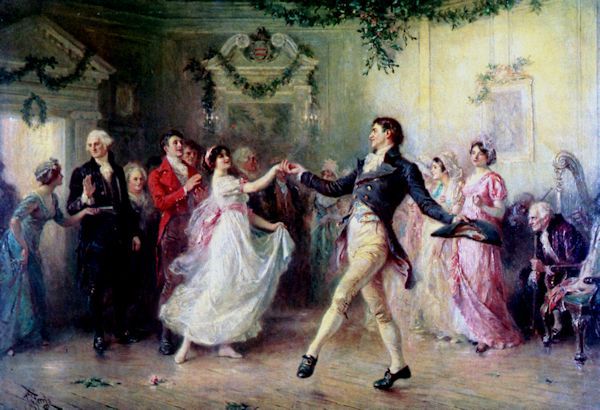

In preparation for coming “out”, dancing was as much a required skill as learning how to manage a household or speaking French. Many wealthy families employed dance masters or “caper merchants” to teach their teenage children how to dance. The dance steps of the day were complex and varied so it was difficult to simply pick up and do it with any sort of grace, form, or confidence.

Dancing reflected on one’s upbringing and manners, which reflected on one’s suitability for marriage. During the Regency, one had many opportunities to dance. Private balls and public assemblies focused on dancing as did masquerades. Almack’s was another coveted venue for dancing but one had to have been important enough to be invited.

Even dinner parties often ended up in an impromptu dance. It required moving of furniture and rolling up of carpets to create a dance floor in the drawing-room or great hall, and a guest or host being willing to accompany the dancers on the pianoforte or harpsichord, then Voilà ! —instant ball.

The most common dances were English country dances (similar to the Virginia reel) the cotillion, and the quadrille. Sometime around 1815, the waltz entered the English ballroom. However, many considered the waltz to be scandalous because it required so much close contact with the opposite sex, and is danced with only one partner. The waltz during this time was what we now refer to as the Viennese waltz, which is lovely and involves a lot of spinning. I had a lot of difficulty with dizziness when I first learned to do it.

A Little Season

Many sources, both fiction and non-fiction mention a Little Season—a smaller social whirl that started as soon as the MPs arrived in London in autumn. However, it didn’t really catch on for the general public until sometime during the Victorian Era.

At Season’s End

The end of the Parliament marked the end of the Season. Most of the fashionable set left London for their country homes, or for their grouse fields (or their friend’s fields) to, “persecute small animals.” My sentiments, exactly. Those who wished for another opportunity to marry off an adult child that year, or who wanted a change of scenery or craved more social events than the country generally provided, went to Bath or Brighton.

Sources:

Regina Scott has the most complete and accurate listing of the dates when Parliament met during the Regency that I have found, as well as details of how Parliament was run here: http://www.reginascott.com/parliament.htm

What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew by Daniel Pool

The Writer’s Guide of Everyday Life in Regency and Victorian England by Kristine Hughes

Georgette Heyer’s Regency World by Jennifer Kloester